Finding New Value in Old Buildings with Adaptive Reuse

Ben de RubertisAIA, LEED AP BD+C, ULI

Ben de RubertisAIA, LEED AP BD+C, ULIPrincipalview bio >

Stuart LewisLEED AP

Stuart LewisLEED APPrincipal,

Plannerview bio >

Chad ZuberbuhlerAssoc. AIA

Chad ZuberbuhlerAssoc. AIAPrincipal,

Plannerview bio >

Nothing stays the same forever. Buildings that were designed to meet an important demand decades ago may have outlived their usefulness because of new innovations or changing economic or societal needs. The first instinct is often to demolish these old structures and build something new. But many outdated or neglected buildings still have value, and with thoughtful planning, they can be adapted and reused to begin a new life.

Finding an older building's value requires design experience and expertise but also careful consideration. Like a good manager, coach, or therapist, it's crucial to listen to what the building is telling you in order to understand its strengths and vulnerabilities and consider what changes and interventions will help a building overcome those limitations to reach its full potential.

Why Adaptive Reuse?There are many reasons why an adaptive reuse project can be a more appealing option than a new build. When funding new capital projects is a challenge, starting with an existing structure saves time and money. In addition, it is often easier to get approval than a new building project of the same scope. Adaptive reuse projects will typically require fewer permitting hurdles to overcome and can offer a quicker timeline.

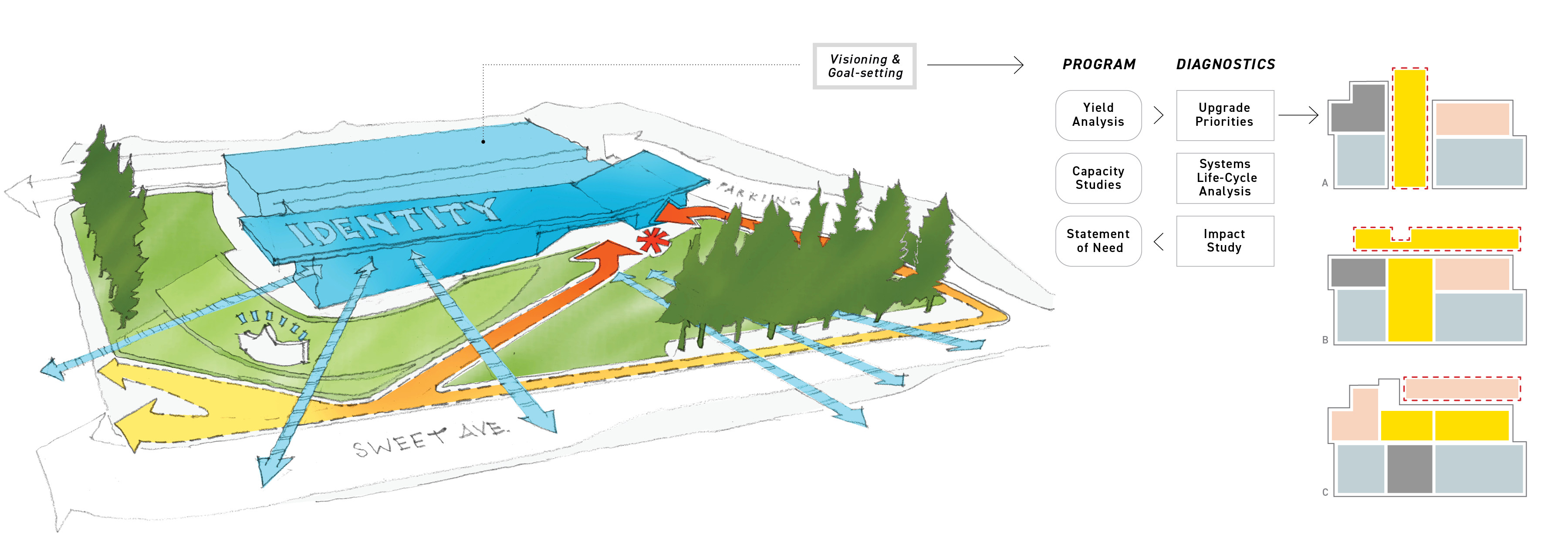

When the scope of a project seems daunting, we've worked with clients to break a project into phases of a micro-master plan. This allows for some spaces to remain operational during the project. It also allows a project to steadily progress with a series of targeted fundraising goals instead of waiting for years to fund the full project. This helps build momentum as stakeholders witness progress.

Maybe most importantly, adaptive reuse is appealing for its lower environmental impact. Adapting an existing structure eliminates the need to demolish an entire building and requires far less energy and new materials to complete.

When it comes to planning and programming, it's important to note the difference between renovation and adaptive reuse. For a renovation, the building is expected to serve a similar function. For example, an office renovation may entail updating the fixtures, furniture, finishes, and even the layout, but it will still be an office building. With a renovation project, it is assumed that the building is already suitable for its function, so any analysis of building performance would simply be to confirm assumptions.

An adaptive reuse project reimagines a building for a new use, such as repurposing a former retail building for laboratory space. Before getting into the specifics of planning and programming, you must first address the question of suitability. This entails more considerations of cost, performance criteria, and the programming scope. More than that, you must ask what can this building hold? Unlike planning and programming a new building, a reuse project has physical existing constraints. Not everything can be squeezed in or bolted on. Early, thorough due diligence to assess the current state of the building will help to set reasonable expectations and potentially avoid wasted effort pursuing a design that won't meet intended goals.

Working BackwardsNew buildings are typically built around building programs, which are developed using industry benchmarks and metrics. However, starting with an existing building requires reverse engineering that process. For an adaptive reuse project, it's best to start at the end, which is the current state of the existing structure, and work backwards to reach those desired metrics. Even when comparing the same square footage as a new build, an older building will inherently be less efficient. Whether it's the existing envelope, utilities, or maybe the placement of an elevator shaft, a building originally configured for a different use will impose constraints. However, that inefficiency will be mitigated by the time and resources saved by reusing the structure instead of demolishing and replacing it. Very early in the project, you will want to start this process of working backwards to determine what will be an acceptable level of inefficiency for the building to be suitable for the intended new purpose.

With that in mind, the building owner and stakeholders should determine the carrying capacity of the project. Simply stated, that is the minimum number of laboratories or classrooms or principal investigators needed to be included in the program to ensure the project's success.

Get to Know the BuildingBefore diving into the details of an adaptive reuse project, the owner and the design team should devote more time to thinking about high-level goals of the project than you would with a typical new build or renovation project. What is the driver for this project? Why is this project important? Why now? How will this project improve your organization? Having good answers to those questions at the start of the project will help the project team to focus on the right things and manage expectations.

First, you'll need to really understand the value of the building. Think about the building's strengths and how it fits within the big picture and the project vision. Don't get sucked into the weeds of programming and schematic design too soon. There will be plenty of weeds to address later.

Working with an integrated design team, this is the time to put on the therapist hat and listen to what the building is telling you to find the value in this existing or newly purchased structure. The design team can help answer the question of suitability, which is fundamentally the ability of the existing structure to effectively serve its new purpose.

One of the most common mistakes we have seen owners make with an adaptive reuse project is overprogramming. It is crucial to understand that the space utilization of an old building will be inherently less efficient than a new building of the same size, and you simply will not be able to fit as much program as a new building. Like a burrito, each additional ingredient may add value, but the shell can only hold so much before it becomes a mess.

The key here, once again, is working backwards. Instead of starting with a long list of program needs and determining how to squeeze them all in, start by looking at opportunities that the building presents.

Similar to overprogramming, another common mistake is over-renewing. There is a temptation to make more updates than necessary in an attempt to make an old building feel new. By replacing or covering up too many existing features, you'll lose the character of the building. The design should merge the building's existing value with its new use, not replace one with the other.

The design should merge the building's existing value with its new use.

Design is a process of evaluation, and especially for an adaptive reuse project, it becomes a balancing act. You'll need to decide what will be preserved, what could be refinished or modified, and what will be torn out and replaced. It's not a simple equation or an exact science. It's more like a giant switchboard where pushing one button impacts the levels of 10 other elements.

Beyond hitting your target metrics, there is also a responsibility to honor the original design intent and the soul of the building. For example, a brutalist concrete office building may benefit from more natural light, but giant stained-glass gothic windows would likely not honor the soul of the building. Again, there isn't always a clear right or wrong answer to what updates are the right fit for a building, but gaining a deep understanding of the building will help guide.

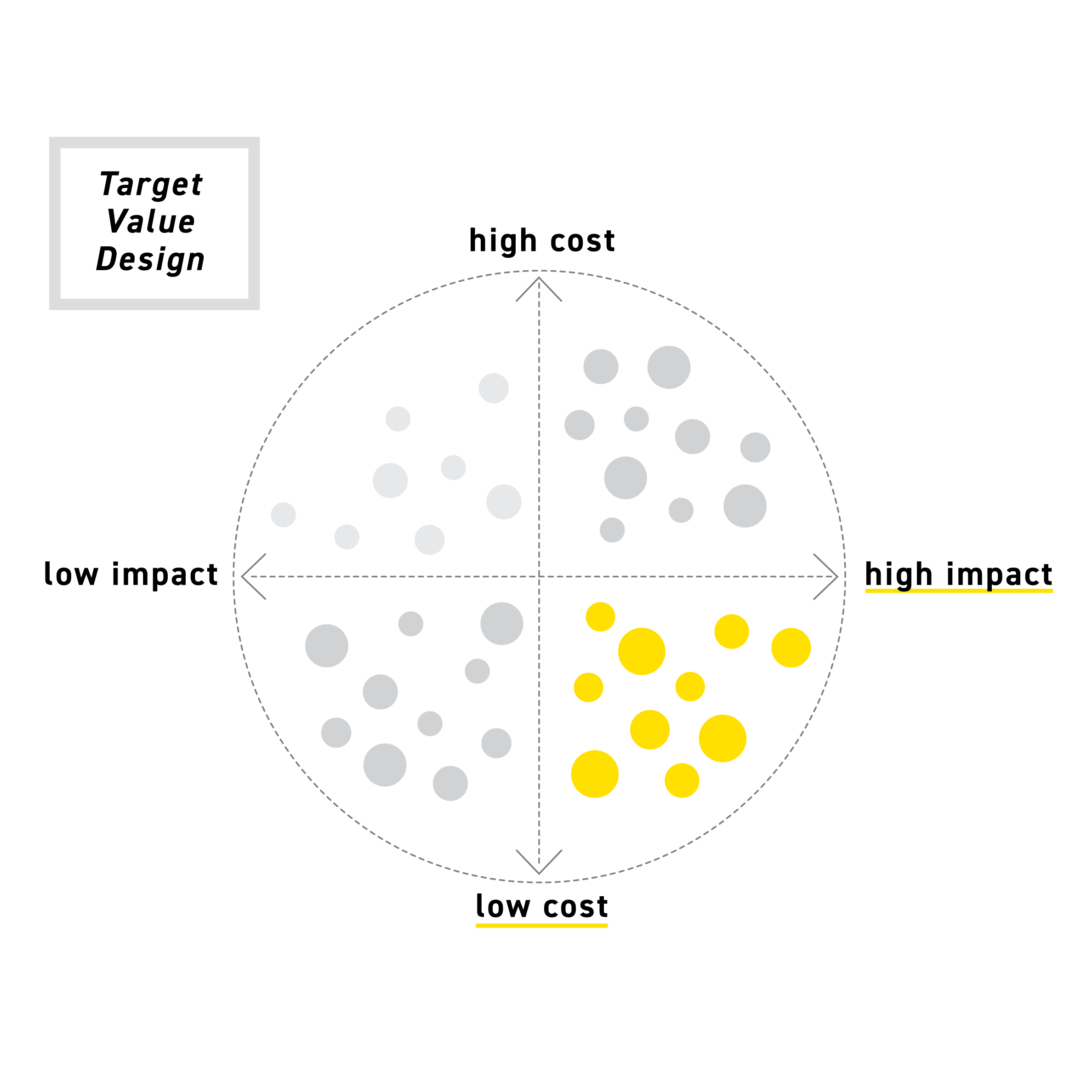

Expect the UnexpectedWhen adapting old buildings, there will be issues and unknowns. A qualified building diagnostician will help uncover issues and provide an objective assessment of the building's condition, including remaining service life of finishes and any systems not up to current code. With a list of issues to address, you'll need to prioritize. Not everything can or should be replaced. That would defeat the purpose of a reuse project. Start with the most pressing issues that need to be addressed for the building to function, such as a leaking roof or a broken window. Then analyze each option based on cost and impact. The upgrades that fall into the low-cost, high-impact quadrant should move to the top of the priority list.

As you work through the building analysis, there will be surprises. The physical structure may not exactly match the original design documents, if those documents are even available. The building envelope may be less energy efficient than assumed. Pipes may need to be replaced. When these issues arise, it's natural to feel a sense of buyer's remorse or worry that it will derail the entire project, but don't be deterred. Through experience, we know to expect the unexpected. Though it may feel daunting, we can assure you that these issues can be overcome. The good news is that with an existing structure, you are much less likely to uncover the type of big unknowns that occur when breaking ground on a new site.

And remember that the building has value. You're not starting from square one with an empty lot or a blank page. The money and resources that are not being spent on demolition and designing and constructing a completely new building can be spent on other things, including addressing unexpected project challenges.

Honoring the Past, Building the FutureWe have worked on a variety of projects of every shape and size, and it's exciting to see the response to a successful adaptive reuse project. There is pride in rediscovering something that could have been discarded and giving it a successful second act.

There is always a sense of satisfaction when a project meets its intended goals. But these reuse projects also tend to bring out an even stronger sense of community and collaboration. By listening to what a building has to say, you can help it tell another story. With an adaptive reuse project, there is an opportunity to not only extend the life of a building but become a part of its legacy.